In Ontario (Attorney General) v. Working Families Coalition (Canada) Inc., 2025 SCC 5, the Court considered the constitutionality of Ontario legislation that limited the amount third parties could spend on political advertising in the year prior to a provincial election.

The five-justice majority opinion recognized the foundational importance of the right to vote protected by s. 3 of the Charter (¶¶1, 27) and found the Ontario statute unjustifiably infringed that right by creating “a disproportionality in the political discourse” between political parties, third parties, and their respective roles in the electoral process (¶¶11, 55, 64). In the dissenting opinions, two justices (Wagner CJ and Moreau J) agreed s. 3 extends to third-party spending but disagreed the right had been infringed and two other justices (Rowe J and Côté J) found s. 3 was not engaged at all.

Each of the opinions at least engaged with the idea that s. 3 protects “the voter’s right to an informed vote and to meaningful participation in the electoral process” (¶13). As Karakatsanis J. explained in detail for the majority:

“…the purpose of s. 3 is for voters to be effectively represented in government, and to play a meaningful role in the electoral process. A legislative measure that undermines or interferes with citizens’ ability to meaningfully participate in the electoral process will infringe the right to vote. And meaningful participation requires that citizens be able to vote in an informed way (Harper, at paras. 71 and 73). An informed vote is foundational to the health of the electoral system and a properly functioning democracy” (¶9, emphasis added).

The majority took a functional approach: the electoral process is settled and known, each type of actor (e.g. candidate, political party, third party) has its distinct role within that process, and s. 3 maintains the balance between those roles so that citizens can be exposed to “the political discourse” and develop an “informed view” (¶¶30-36). Clearly, this approach relies on certain beliefs about the necessary and proper institutional settlement for our constitutional democracy. Karakatsanis J. even invoked the classic cornerstone for that basic constitutional structure: Reference re Alberta Statutes, [1938] SCR 100 (¶31).

Since we’ve covered structural analysis in some detail, perhaps more interesting is a curious omission from all three opinions: focused as they were on doctrinal details and institutional design, the Justices gave no consideration to voters’ capacity to understand the information disseminated by third parties, let alone their ability to discern the political issues that define their community (¶13) and develop the views that depend on institutional equilibrium (¶55) in the Court’s “egalitarian” model of the electoral process (¶32).

According to the majority, the s. 3 right of Canadian citizens to meaningful participation in the electoral process can be infringed by disproportionate restrictions on third parties’ ability to purchase advertisements. Could that right also be infringed by widespread illiteracy and profound innumeracy among Canadian voters?

Our s. 3 right to meaningful participation in the electoral process is exercised and assessed in a particular institutional and social context. As the majority wrote at para. 2: “The right to vote is more than ‘the bare right to place a ballot in a box.’ It is exercised within a framework of institutions and actors, including regular elections and sittings of the legislatures guaranteed by ss. 4 and 5 of the Charter, political parties, candidates, campaigns, electoral districts, laws regulating conditions for voting, and more.”

“More” must include our fellow citizens, right? They are mentioned in the text of s. 3. Individuals use information not in blissful isolation, but together in organizations, groups (vulnerable, marginalized, and otherwise), and community (e.g. ¶¶4 and 9). The issues that define our community (¶13) do not exist ab initio. They are developed and contested by individuals exchanging information with one another. The capacity of individual citizens to assimilate and produce information is the vital, unspoken assumption behind the egalitarian model of the electoral process elaborated in Working Families Coalition.

Nearly half of Canadian adults struggle with literacy. In 2022, 49% of Canadian adults scored Level 2 or belowon the OECD’s Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competences. At what point is our blessed equilibrium undone?

I understand this issue was not presented by the case in Working Families Coalition, but I remain deeply concerned that the Court is not attuned to the nature and extent of our illiteracy problem.

The majority claimed “…the electoral process is the ‘primary means by which the average citizen participates in the open debate that animates the determination of social policy’ (¶28, citing Figueroa, ¶29).” The turnout in the February 2025 Ontario provincial election was just 45.4%. The “average citizen” did not bother to vote, which presents a serious problem for the model of legitimacy espoused by the majority, in which the right to vote “is the basis of the legitimacy of laws enacted by lawmakers as ‘the citizens’ proxies’ and a vital incident of Canadians’ membership in a self-governing polity” (¶28).

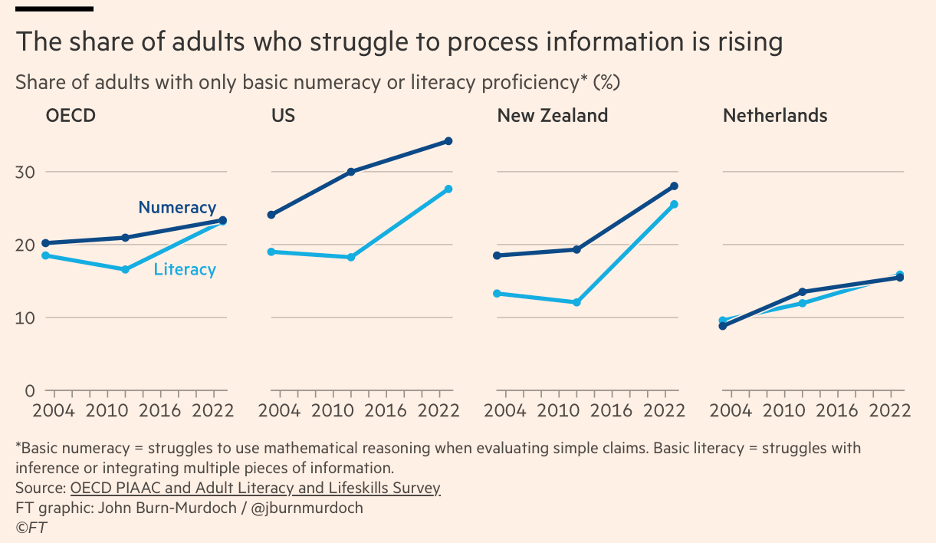

As recently highlighted by John Burn-Murdoch in the Financial Times, Canada is not alone in this mess. Adult literacy and numeracy are in rapid decline across the OECD: “the share of adults who are unable to “use mathematical reasoning when reviewing and evaluating the validity of statements” has climbed to 25 per cent on average in high-income countries, and 35 per cent in the US.”

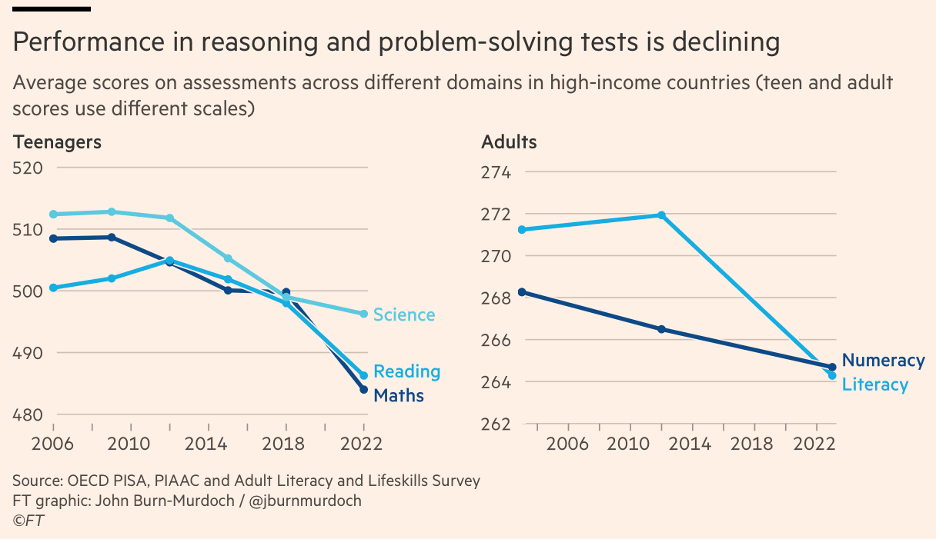

Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) scores confirm this degeneration afflicts teenagers as well as adults:

But what to do? To start, we should recognize and investigate the obvious inflection point around 2012. Our democracy is under threat, not only from below but also from within. We are losing the basic skills of literacy and numeracy that enable us to hold our governments accountable and to exercise the s. 3 right that is “foundational to our democracy and the rule of law” (¶27). As our governments take radical steps to counter our increasingly erratic and belligerent neighbour, we must advocate for real investment in Canadian citizens: the true foundation of Canadian democracy. We must also develop more creative and effective arguments to ensure our Constitution can meet these “new social, political and historical realities” that were certainly “unimagined by its framers” (Hunter v. Southam, [1984] 2 SCR 145, p. 155).

If my s. 3 right to vote protects the ability of unions to buy TV ads, then why can’t it also protect my fellow citizens’ right to read, which is threatened not only by counterproductive pedagogy and inattentive educational bureaucracies but also by poorly regulated “social media” and ill-consideredfederal funding cuts?

Leave a Reply