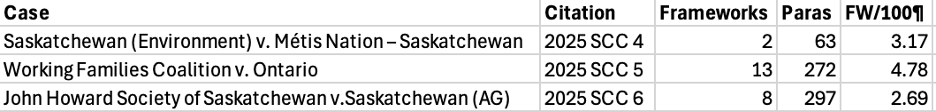

Framework frequency remains low, even unremarkable, in the young 2025 term.

Of course, numbers never tell the whole story. When we look closely at how the Justices have used frameworks this year, we can see just how critical this concept has become to their understanding of the law.

In Working Families Coalition, Karakatsanis J wrote for the majority: “This Court has long recognized that s. 3’s protection must be interpreted broadly and extend to the conditions under which the right to vote is formally exercised. The right to vote is more than “the bare right to place a ballot in a box”. It is exercised within a framework of institutions and actors, including regular elections and sittings of the legislatures guaranteed by ss. 4 and 5 of the Charter, political parties, candidates, campaigns, electoral districts, laws regulating conditions for voting, and more” (¶2, citations omitted, emphasis added).

Last term, we talked about two types of framework used by the court:

- Legal frameworks, which are established by or described in legal instruments, and

- Analytical frameworks, which are developed by courts to understand and apply those legal instruments

The majority opinion in Working Families Coalition revealed a third type: metaphorical frameworks, which are used to characterize other phenomena and influence our understanding of them. In this case, Karakatsanis J. characterized the electoral process as “a framework of institutions and actors”, which implies a measure of order and predictability that political actors may dispute.

The metaphor of a framework facilitates structural analysis and minimizes individual agency by emphasizing known processes, fixed roles, and essential balance at the expense of subversive actual experience. Projected beyond the courtroom, this metaphor is a mechanism of control: it frames the world as fundamentally similar to the law. We can know it, define it, predict it, and manage or even manipulate it. The framework metaphor also reinforces a privileged role for courts: to the extent other domains resemble the law, then it is appropriate for legal experts to define and dominate them.

Dissenting in John Howard Society, Côté J. observed that a precedent is “unworkable” and ineligible for stare decisis if it undermines the rule of law, and she explained further that “[t]he rule of law will be undermined when a precedent makes the law indeterminate or subject to a judge’s personal preferences, rather than a principled framework” (¶165, emphasis added). Here, Côté J. used “framework” in a normative sense to describe what the law is and should be: ordered, transparent, justifiable.

She cited Vavilov, but this part of Côté J.’s opinion reminded me of the classic passage in Hunter v. Southam: “A constitution, by contrast, is drafted with an eye to the future. Its function is to provide a continuing framework for the legitimate exercise of governmental power and, when joined by a Bill or a Charter of Rights, for the unremitting protection of individual rights and liberties. Once enacted, its provisions cannot easily be repealed or amended. It must, therefore, be capable of growth and development over time to meet new social, political and historical realities often unimagined by its framers. The judiciary is the guardian of the constitution and must, in interpreting its provisions, bear these considerations in mind” (p. 155, emphasis added).

The Court’s framework fixation runs deep. Apparently, so does mine.

Leave a Reply